I didn't used to believe that Spaced Repetition Systems like Anki were that useful for the kind of knowledge that I wanted. I believed they worked, in the sense that they could help you memorize whatever you wanted very efficiently, but my goal was grokking, that powerful form of deep understanding, and I didn't see how rote memorization would help. I now think Spaced Repetition Systems can be really useful in helping you grok something, and am very excited in their potential to make this form of learning inevitable, and make it last forever.

Spaced Repetition in 60 seconds

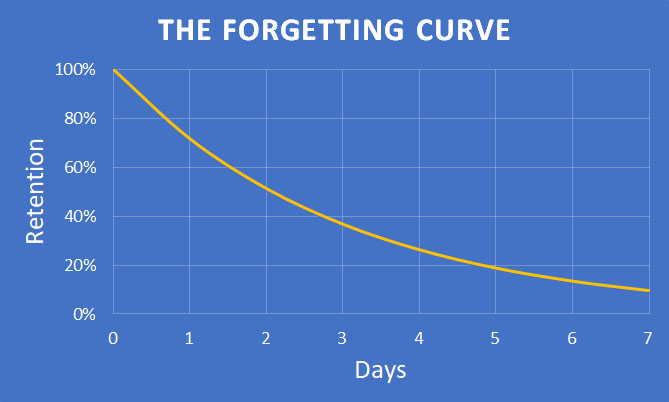

If you're not familiar with Spaced Repetition Systems, I highly recommend you take a few minutes to read this lovely illustrated blog post for a primer. But as a refresher, experiments show our memory of a piece of information decays in a way that looks like this:

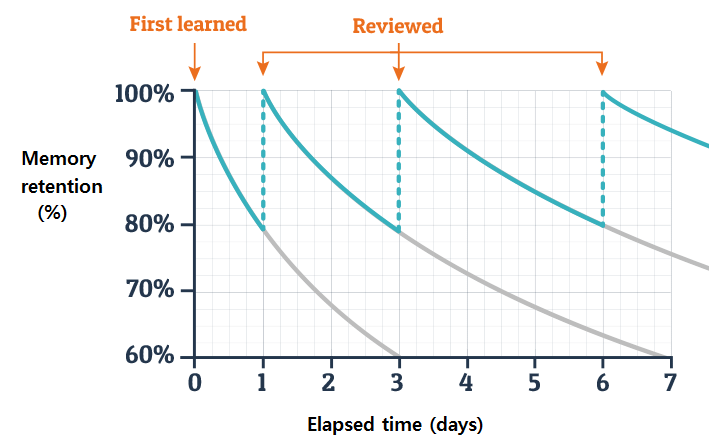

We can reinforce our memory of a piece of information by forcing ourselves to recall it.1 The amount of time between recalls is the spacing. Because our memory of something gets a bit stronger each time we recall/practice it, it's efficient to use an expanded spacing strategy:

This is the main idea behind Spaced Repetition Systems (SRS) like Anki, which are basically flashcard apps that take care of the spacing algorithm for you. The value proposition is: "you can add 10-30 cards/day of new information and, with 10-20m of review a day, remember that information forever".

Grokking is the holy grail of learning

In my model of learning, grokking is the holy grail. When you've grokked an idea, you understand it well enough to comfortably explain it to others, re-derive it yourself, make connections with other ideas, etc.

When you grok an idea, you're building an understanding that is...

- highly compressed. This is great because humans have fairly small working memories, and compressed representations free up space for other ideas and reasoning.

- highly connected to other ideas. Our minds are association machines, and connections between ideas are vital to ideation and reasoning. Highly connected ideas are also much stickier, as activating adjacent ideas can trigger recall.

It's easier to grok new ideas when you've grokked related concepts.

For example, if I'm learning what a gradient is in multivariable calculus, this idea is much easier to wrap my head around if I have a solid understanding of what partial derivatives and vectors are. If I don't feel intuitively comfortable with both of those concepts, I'll have to expend effort and working memory building up mental representations of those objects independently, and will have little left over to combine them and play with the result. If I've grokked partial derivatives and vectors, I can easily combine them and ask how the properties of the derivative and vector compose. I might notice that the dot product of a direction with the gradient gives the rate of change in that direction by combining the linearity of the derivative with the fact that dot products perform a linear combination. This sort of jump would be tricky without having previously internalized intuitions around partials and vectors.

In fact, I believe almost all individual jump between concepts are fairly small. Much of the time when something is hard to grok, it's because there's an important related idea that you haven't fully internalized yet that is a little too big to fit comfortably in your mental space with the new information.

And this is where repetition comes in.

Repetition can aid grokking

Some ideas are resistant to grokking on a first encounter. But being exposed to an idea multiple times, especially spaced over time, makes it easier to grok.

Repetition aids grokking for multiple reasons:

- Ideas requires time to fully internalize. Consolidation (which occurs while you sleep) is when a lot of the actual compression and connection-building happens. So coming back to an idea again often means you're in a slightly better spot to understand it.

- We're most likely to make headway on understanding something within the first few minutes of thinking about it. I think of this as similar to how it's useful to randomly restart heuristic search algorithms sometimes so they don't spend all their time in an unfruitful part of the solution space.

- If your system for repetition also contains the pre-req concepts for an idea, you'll grok them further, making it easier to grok follow-up ideas.

A concrete example: I've been learning matrix calculus recently, and made some cards on how the chain rule works for Jacobians. Importantly the point of these cards isn't for me to memorize the front-to-back mapping. Rather I've designed the cards to help me practice internalizing these ideas over time. When the cards come up for review, I re-derive the answers from previous knowledge instead of memorizing a mapping based on superfluous details.2

Inspiration

- things I'm excited to learn via Anki

- Math

- Card archetypes: definitions, exercises (generated?), proof steps, intuitions, canonical examples

- Computer stuff (how the rust compiler works, what ABI vs. ISA specifies)

- Card archetypes: terminology, design motivations, key design choices

- All the neat stuff in the books I read and forget about a few months later...

- Math

- advice on how to write good cards

This is in line with a general pattern in learning that effortful methods (active recall) beat out passive ones (ex. re-reading)

Although I admit that crafting good cards is definitely a skill. Something I hope to get better at with time.